Dengarkan Artikel

Dr. Al Chaidar Abdurrahman Puteh

Department of Anthropology, Malikussaleh University, Lhokseumawe, Aceh

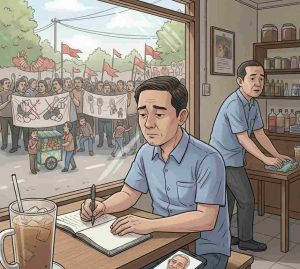

In Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra, the floods and landslides that swept away villages, severed bridges, destroyed roads, and carried houses downstream were not simply “natural disasters.” They were the consequence of policies and corrupt networks that stripped forests bare, converted landscapes into belts of commodity production, and displaced ecological protection in favor of national revenue. The torrents of water carrying cut logs were the most visible archive of destruction: trees that should have held the soil and absorbed the force of rainfall became physical evidence of systemic exploitation. When communities demanded the state’s protection, what they received instead was minimal rhetoric, bureaucratic reluctance to declare a “national disaster,” and a shifting of responsibility onto “extreme weather” or “local conditions”—as if trees fell without anyone cutting them down.

The facts are undeniable. Floodwaters carried timber and debris, clear signs of deforestation in upstream areas. Hydrological science is straightforward: when forests vanish, infiltration decreases, run-off accelerates, slopes lose their anchors, rivers lose their buffers, and water energy is released unchecked. The material evidence after the floods—logs piled against bridges, channels blocked by timber residue—demonstrates that deforestation is not speculation but a visible cause. Concessions, permits for land clearing, and palm oil expansion in hydrologically sensitive terrain confirm the link between extractive economies and hydrometeorological disasters. Calls for police investigations into the origins of the timber are not merely legal demands; they are appeals to restore accountability chains broken by collusion and rent-seeking.

For decades, the logic of “national revenue” has treated Sumatra’s forests as a commodity bank: timber, pulp, and later palm oil. Permitting regimes, fragmented governance, and selective enforcement opened space for clearing natural forests, converting peatlands and mountain slopes, and disregarding ecological thresholds. On paper there are environmental impact assessments, zoning rules, and prohibitions. In practice there are loopholes, regulatory compromises, and institutionalized neglect. When ministers push production targets and plantation expansion without considering hydrological capacity or fragile topography, those decisions cascade downstream as risks converted into losses borne by citizens. Corruption—whether overt or normalized through weakened regulations—functions as the lubricant that makes destruction appear as ordinary business.

Ann Laura Stoler’s scholarship helps us see that this devastation is not merely technocratic but affective. In Capitalism and Confrontation in Sumatra’s Plantation Belt, 1870–1979 (1985), Stoler revealed how colonial and postcolonial regimes in Indonesia used plantation economies to discipline and marginalize local populations, embedding exploitation within governance structures. In Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (2009), she examined how states construct knowledge and bureaucratic practices that normalize domination, showing how archives and “common sense” produce reliable silences.

📚 Artikel Terkait

Within this framework, the “affective state” does not simply regulate; it manages feelings—care, empathy, security—selectively. It mobilizes the language of protection for commodities and capital, but withholds empathy from marginalized citizens and peripheral regions. It loves forests as revenue but allows rivers to punish communities when rains intensify. It records victims as “local” to avoid national obligations, naming floods as “seasonal” so structural accountability remains untouched. This is affective predation: extraction cloaked in development rhetoric, while suffering is normalized as an unnamed cost.

Aceh, North Sumatra, and West Sumatra each bear the weight of this logic. In Aceh, forest clearing for palm oil and timber has destabilized watersheds, making landslides inevitable even on slopes once stable. In North Sumatra, the mosaic of concessions and monoculture plantations erodes ecological heterogeneity, cutting water corridors and faunal pathways so floods become channels of violence. In West Sumatra, steep topography that should be protected is burdened with conversion and infrastructure without adequate ecological mitigation. When bridges collapse and roads wash away, these are not “natural surprises” but consequences of policies that ignored hydrological science and environmental justice. More painful still, when the scale of destruction demands national mobilization, the central government chooses classifications that minimize obligations. The message to citizens is simple: your resources are our concern, your disasters are yours alone.

Naming floods and landslides as “man-made disasters” is not political rhetoric; it is ethical precision. It demands tracing the origins of timber debris, auditing permits that violated protected landscapes, and exposing financial flows that sustain deforestation. It requires clarity in governance: moratoriums in vulnerable zones, restoration of strategic forest reserves, watershed rehabilitation grounded in science, and restructuring economic incentives so they no longer reward destructive conversion. In Stoler’s horizon, reform is not merely rewriting regulations but dismantling the bureaucratic “common sense” that treats victims as statistics and commodities as primary citizens.

The floods and landslides in Sumatra are mirrors of the affective state gone astray: a state that cherishes profit while sacrificing the lives of its minorities, its remote populations, and its voiceless communities. If the state wishes to abandon predation, it must restore affect in the right direction: empathy that is equal, protection that is not selective, and accountability that is non-negotiable. Recognizing disasters as national when their scale demands it is not mere administration; it is a declaration that citizens matter more than commodities. In Stoler’s language, shifting archives, feelings, and bureaucratic common sense is a prerequisite for dismantling the durability of power that produces silence. Without such transformation, every rainy season will write its own archive: trees laid down as witnesses, rivers delivering indictments, and communities forced to read texts authored by a state that refuses to acknowledge them.

🔥 5 Artikel Terbanyak Dibaca Minggu Ini